It would be safe to say that during the testing times of the pandemic, it was the drumstick that became my saviour.

No, I am not talking about the slender pieces of wood that help me make music on the drums. I am speaking about the drumstick hanging like muted chimes on the Moringa tree in my neighbourhood.

Also known as Saragvo in Gujarati, Muringyakaya in Malayalam, this hardy fruit-bearing tree made sure my family never went to bed with an empty stomach during the lockdown.

As the days of scarcity, and uncertainty reeled on with subsequent lockdown extensions, the majestic Moringa tree in the park assured us of our food security.

The moment the sun beamed its first rays into our locality, my mother would silently make her way to the park with a long stick in her hand. After some hustling, she would be back home with a few drumstick pods and a bunch of moringa leaves.

Come lunch and we’d have a spread of sambar and rice. Without the succulent drumstick soaking in the lightly flavoured stew, the dish would pass off as dal. But its pulpy goodness, and the satisfaction of sucking on the last drip from its fibrous remains made us feel a sense of plenitude in times of utter scarcity.

However, the spice shelf soon ran out of the indispensable ingredient of sambar – tamarind.

But has the creativity of a mother ever failed us?

Each day, we’d get to taste a different kind of tanginess in our ‘sambar’. We tasted the flavour of dried raw mangoes, dehydrated amla, Malabar tamarind, lemon, or even Kokum, as a replacement for the usual tamarind spiced sambar. And each dish would outdo the one served a day earlier.

The drumstick leaves started featuring in plenty in our dishes, sometimes as saag,at times as a poriyal with grated coconut, as a leafy accompaniment in dal, at times just raw as a garnish on a cucumber and pomegranate salad.

It’s safe to say our home was suffused with the aromatic blessings of the Moringa tree.

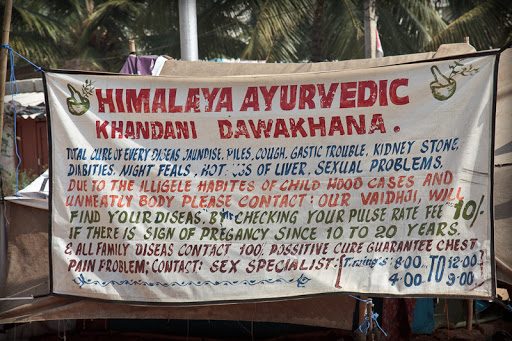

Since we were consuming so much food from a single tree, we wondered if there were any side effects to it.

After some searching online, my mother said,

‘They say it’s a superfood. Do you know anything about this? What is a superfood?’

I could have looked it up. But after the generous care given to our family for two months at a stretch, could I deem its superfood status merely to some magical combination of micronutrients?

Towards the end of May, the drumstick on the tree began to dry up. Only a few dozen drumstick remained near the canopy. But when my mother’s height failed her to reach the topmost fruit, my father’s resolution helped bridge that slender distance.

We derived as much as we could from the tree, until the day it rained for the first time in the season. With a grateful heart, we let the tree heal and recover with the spells of rain to follow.

From the last few drumstick, my mother managed to grow a few saplings. They’re growing well, one each on either side of the entrance to our home.

I remember how during the summer months, our city would be full of drumsticks hanging from the ubiquitous Moringa trees. But all of that fruit dried up every year, without ever receiving respect through our consumption.

The dried seed pods would fall on the concrete pavements. Not one seed would manage to break the opaque, unyielding shield of modernity and reach a longing layer of soil beneath.

I haven’t been out on the streets lately due to the pandemic.

But I only hope that all other Moringa trees have been utilised as abundant treasures in times of scarcity. I hope all of them look like the resurgent tree in our park, one that’s grateful of having served its cause, of having saved a few lives.

And if there are other seeds that have blossomed outside the houses of our unknown neighbours, the hapless seedlings have finally found a fertile place in our heart.