A fabric that we spend the most time choosing yet spend the least time looking after, would undoubtedly be the good old curtain. We invest an entire day to get the right shades, get them stitched with utmost care and yet, once installed, we forget all about them. They set the mood for our homes but accept our forgetfulness and neglect in return. Such is the life, of these soft, overhung draperies.

To a room that otherwise houses a stationary assemblage of inanimate things, the curtain adds a sense of quiet motion. Subliminally, a curtain serves as a company. Sometimes, even while being alone inside a house, when the curtains sway silently, we choose to believe that outside, somewhere far away, someone beautiful is breathing.

When it comes to functional utility, the curtains punch way above their feathery weight. Curtains serve as the best sunscreen. They let us customize how much daylight we wish to let into our rooms. In the process, they trap floating dust motes in their fabric fencing, letting us breathe cleaner air. Apart from the utility, curtains also serve as a subtle implication for the need for privacy. When we draw the curtains in, the world outside grants us the time and space we need.

Children extract value from the curtains in their own sweet way. While most adults hide behind curtains, kids choose to hide within them. If a curtain is long enough, the fabric becomes the fortress that conceals every bit of the little one, but its tiny feet. However, more often than not, it’s their giggling that gives their location away to the one searching for them.

The curtain fosters the dream of being Tarzan in kids, a dream that often ends with a tough bum-landing on the floor. Kids take time to wean of from their mother’s pallu. The curtain serves as the sanctuary of snot and tears during this phase of life when the wailing kid fails to extort sympathy out of the family. And this habit stays with us at a subconscious level. We have to hold back our reflex of wiping our hands with the curtain, lest someone is watching. Couples living together deter each other from doing this, while exercising restraint themselves to commendable heights. Only kids enjoy free reign. And now you know why curtains show up on clotheslines of families with kids every other weekend.

Meanwhile, the curtains at a bachelor’s home weep silently, lamenting their fate. While these sullied fabrics look out of the window, they see clean curtains drying in the shade across the street. They feel imprisoned behind the bars of the window, abused by a jailer, who by all means, still lives like a child.

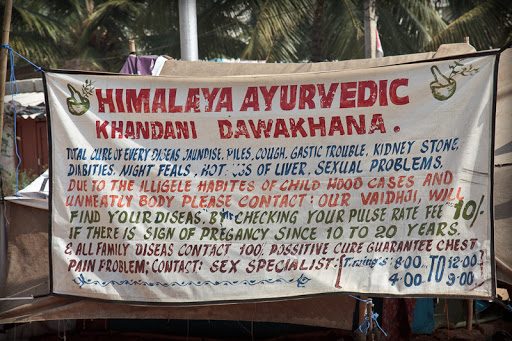

The bachelor chooses to believe that the sun and the wind cleanse the curtains just fine. In this putrid penitentiary, the curtains face criminal neglect. There’s an effort that goes into removing the curtains from the bars. Clearly, product designers have designed these mechanisms without considering the laxity single ageing adults are capable of. As a consequence, the curtains gather dust in a corner, beside a broken flower vase that has by far, never housed a real flower.

While cotton has been the preferred fabric for a curtain, there’s a new fashion wave in the way we adorn our windows. Synthetic materials, cut into precise rectangles, blind the in-dwellers in most office spaces. There’s a good reason why these synthetic curtains are called blinds. They are designed to blind people on either side of the window. Perhaps these blinds are used more in places where adults work, because here, most people feel safe only while crying on the inside. Emotions are subterranean. And so, it is easy to get away with a sterile, non-absorbent cotton curtain…

(Yes, we have wept into curtains at some point in our life, haven’t we!)

The curtains play roles that are too subtle to be noticed by a casual observer. There’s a beautiful way in which this simple overhung fabric enables our expression. Just how a curtain raiser event promises to unveil a motion picture or a stage play, so does a curtain-raiser back at home. The world outside with all its nuance and motion is screened within the frame of the window. It’s a free show for all spectators. And just in case we wish to dance alone or in the company of friends and family, we can draw the curtains in and play an actor without inhibition. When you wish to have a private show, you can draw the curtains in, when you wish to witness the spectacle outside, you can draw the curtains out. One can choose to be a spectator or an actor. Who could tell a piece of fabric could affect our motions and emotions to this degree!

Curtains are the silken veil our demure domestic selves hide behind to smile and dance in assumed safety.

With all the levity associated with a curtain, it also serves as a grave reminder of social exclusion in the past few centuries. With the establishment of the Delhi Sultanate in India, the ‘Purdah system’ became prevalent in many parts of the subcontinent. Women were expected to hide their faces behind the veil, as a mark of respect to elderly men. Muslim rule in Northern India influenced Hindu upper classes to follow a similar practice. ‘Beauty must be guarded behind a veil’ was the rationale. Be it a burqa or a ghunghat, women were the casualty. Some proponents of the practice viewed it as a means of judging a woman by their inner beauty rather than physical beauty! As a consolation, the women of the working class were exempt from the purdah. Who would harvest grains if the lower-caste women don’t go to the fields! And it was work that helped these women get a clear view of the sky under the unforgiving tropical sun. A little freedom in inherited bondage.

Bollywood has its own fascination with the word purdah. Many iconic songs use it as a metaphor in the lyrics. Be it ‘parde me rehne do’, imploring to hide a secret behind a curtain, ‘humse sanam kya parda’ where the lover invites her partner to drop his guards and become one, or the Qawaali of Rishi Kapoor as Akbar, who swears to unveil the purdanasheen, else his name be changed!

The curtain is the only piece of fabric that is almost always in motion. A curtain sailing and drying on a clothesline by the river exhibits a palpable joy, one that speaks of savouring a greater freedom, of dancing under the open sky.

The best curtains though are the ones weaved out of leaves. Nothing filters sunlight better than a lush canopy. The Japanese have a word for it, Komorebi.

If you have a good outgrowth outside the window, be it from a screen by vines or by a Mayflower tree in bloom, you can enjoy your privacy and a scintillating view without needing to draw the curtains in or out.

The leaves purify the air and change shades with seasons. They host the play of squirrels and the song of bulbuls. The rain rests on them while falling and the wind dances to their touch. A priceless combination of view and functionality, gifted to us for free by nature. I might as well say, directed so elegantly by nature, this play surely deserves a rousing curtain call!

But rarely do we care for this gift. The other day, I noticed an unusual flux of bright light illuminating my room. As I peeped outside, I noticed the absence of green in my view. The annual pre-monsoon pruning of trees had begun. And in the process, I had lost the liberty to dress down to my comfort. The trimmed trees decreed me to not roam at home without pyjamas. The clotheslines of the entire neighbourhood were up on full display in their balconies. And I finally saw the face of my new neighbour across the street, who was hidden behind the canopy for the past few months. Her beckoning smile seems to be the only consolation.

Nevertheless, I have my reasons to weep. It’s monsoon. The clouds weep with me. They shower down and invite the tree to grow with renewed vigour. The curtain of the community is getting greener by the day, one leaf at a time. Dressed in my pyjamas, I lean on my window sill.

It’s drizzling. A bulbul chirps.

I wipe my eyes with the soft cotton curtain.

I can only be grateful.